Sudan‘s war is now in its fourth month, with both the Sudanese army and its enemy, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), still convinced they can win.

From the beginning, the warring parties have sought support from outside powers, while looking to portray themselves as the sole legitimate military representatives of the Sudanese people.

Assistance from foreign states may end up being decisive on the battlefield. But civilian movements inside Sudan will also be crucial, both while the fighting continues and for whatever follows a ceasefire.

The army and RSF are courting different civilian groups, while those same political movements are also looking to exert control over the warring parties.

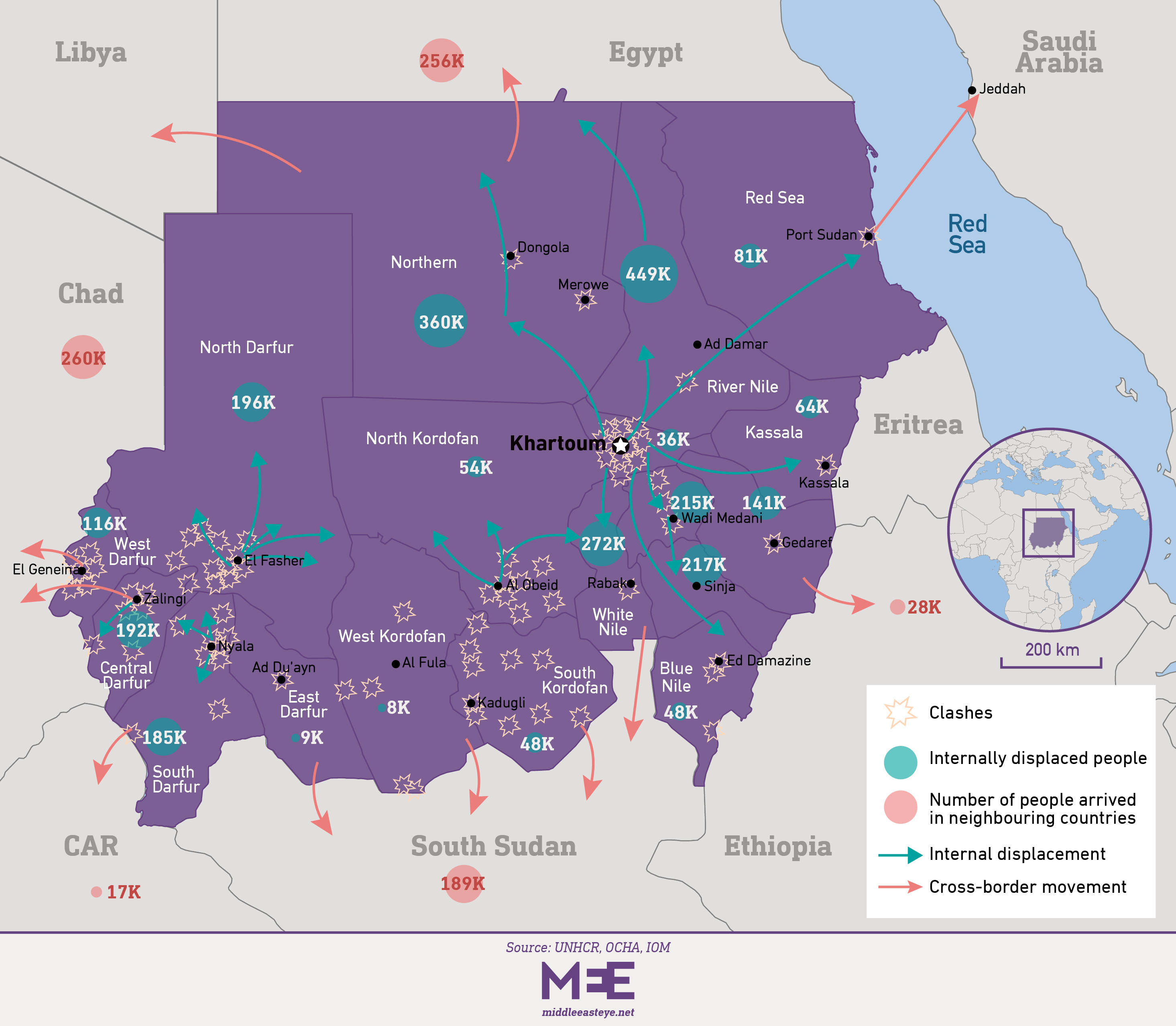

The influence of prominent figures linked to the administration of former autocrat Omar al-Bashir and movements connected to it has been growing in Sudan, as the country’s civilian actors take different positions in the war, which has seen 3.5 million people displaced since 15 April, when fighting erupted in Khartoum.

Politicians connected to the Muslim Brotherhood, the transnational political Islamic movement, and senior figures from the former ruling National Congress Party (NCP), which was officially banned in November 2019 after Bashir was removed from power in April that year, have lined up behind the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

Leaders of the pro-democracy Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition, meanwhile, have been accused of standing with the RSF, which since October 2022 has self-consciously positioned itself as a champion of democracy in its public messaging.

Two separate sources close to the civilian political coalition told Middle East Eye that some FFC figures believe the paramilitary is their best hope of taking power in Sudan.

Each side is fighting a messaging war, seeking to establish its version of events as the truth. The alleged presence of figures from the Sudanese Islamic movement within the army’s ranks has been a key feature of RSF propaganda, with one paramilitary adviser telling MEE the army had formed an “alliance with Isis (Islamic State) and the Islamist battalions”.

The army has also been tied to the deep state of Bashir, a military officer who ruled Sudan from 1989 to 2019, after being brought to power in a coup back by Sudan’s National Islamic Front, the Islamic revival movement that preceded the NCP.

The RSF knows that many Sudanese fear – or believe – that the old regime never really went away, and that Bashir’s men and those who support them have been waiting for a way back to power.

In a speech released by the RSF on its social media platforms last week, paramilitary leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti, told his troops that their enemy was being led by the “deep state and Islamists”.

“We have to be clear that those people [the army] are working under the command of Ahmed Haroun, Ali Ahmed Karti and Osama Abdallah and the other Islamists,” Hemeti said, referring to a trio of senior Bashir-era figures.

Standing between the warring parties are the resistance committees, the grassroots democratic groups that have driven Sudan’s ongoing revolutionary movement and which were integral to the removal of Bashir in 2019.

The committees are strongly opposed to the RSF but do not actively support the army. They call not only for the dissolution of the RSF, but also for widespread reform within the army’s leadership and its return to barracks.

In the meantime, the war rages on, with violations taking place in territory controlled by both sides. An arrest campaign is ongoing in army areas, while MEE has reported extensively on atrocities – including rape, looting and murder – committed by the RSF and its allied militias, particularly in Darfur.

Army recruitment drive

The army has opened dozens of military camps across Sudan after its leader, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, called on young people and anyone else capable of fighting to enlist.

On its social media pages, it has intensively campaigned to recruit young people wishing to fight the paramilitary. The platforms feature hundreds of videos of young men doing exercises and firearms training, and feature songs, national slogans and anti-RSF chants.

Army commanders are also seen making fiery speeches denouncing cases of rape, looting and other violations committed by the RSF.

But resistance committee sources in River Nile, Northern and Red Sea States told MEE that former NCP officials are involved in the recruitment campaign, and that former Sudanese intelligence and security agents are participating in the training.

One source, who is currently undergoing army training at the Jabal Awliya military base, said he believed that the army’s leadership and the Muslim Brotherhood are working together on the recruitment campaign.

“What I have seen in our areas is that the citizens, especially the youth, have a spontaneous reaction against the violations of the RSF, so hundreds of them have joined the military camps, but I noticed that the Islamists are exploiting the anger to mobilise for themselves,” the source, who asked for anonymity, told MEE.

Raad Ibrahim, a resistance committees spokesperson, told MEE that they are rejecting this widespread recruitment campaign, describing it as one of the crimes of the Sudanese Armed Forces.

“The army is putting out widespread populist and nationalist propaganda and using local leaders and tribalism to recruit for SAF,” Ibrahim said. “We are warning that this will drag the country into a wider civil war. Since Sudan’s independence, SAF has only protected those in power.”

The army has not responded to MEE’s questions about the number of camps and the number of new soldiers that have graduated after the opening of the camps.

A military source said more than 50 military camps have been opened across Sudan, receiving thousands of people from states including Khartoum.

The source added that some of those recent graduates are already participating in the protection of key strategic locations.

Ahmed Osman, a military expert, said that the new recruits are too young to join the war against the RSF, and that the army wants them to bolster its legitimacy, rather than for any actual fighting.

“The army is looking for more legitimacy for its war, not for untrained young ground forces. But if the army does put them into battle, that may cause widespread losses,” Osman told MEE.

Bashir-era leaders appear

At the same time, significant figures from the now outlawed NCP have reappeared across the country, including in Kassala and Gedaref states in eastern Sudan. Their presence is inflaming the situation, eyewitnesses told MEE.

Authorities in Kassala have issued an arrest warrant for fugitive leaders, including Ahmed Haroun, a minister in Bashir’s government and the former governor of both South and North Kordofan states.

Haroun, who was the head of the NCP, is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity. In the chaotic days that followed the start of the war, he was released along with thousands of others from Khartoum’s Kober prison.

Following his release, Haroun voiced his support for the army, and referred to Hemeti and his brothers when he described the RSF as a “family project” to rule Sudan.

“The army has got clear and open support from the Muslim Brotherhood, that could be seen clearly on 24 April when the leaders of the NCP were enabled to flee from Kober prison and even made a speech supporting the army,” Mohamed Badawi, a Sudanese scholar and department head at the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies, told MEE.

“We believe that the current chaotic atmosphere is the suitable time for the old regime associates to appear,” Ibrahim, the resistance committees’ spokesperson, told MEE.

“They are also using local leaders and stoking tribalism to campaign for the army and themselves. So, the current situation is not surprising us, as we believe that the Islamists are leading the scene from inside the prison and with the help of the army leadership”, he said.

In the video published by the RSF, Hemeti accused the NCP figures of leading the war against his paramilitary and of mobilising “political Islamists” to fight for the army.

Alongside Haroun, he mentioned Ali Ahmed Karti, foreign minister under Bashir, one of the richest men in Sudan and formerly the unchallenged leader of the country’s Islamic political movement.

Karti, commander of the Popular Defence Forces (PDF) paramilitary in the 1990s, was believed to have regained some influence even before the war began, and is now said to be making the most of the opportunities the fog of war has created.

Khogali Hamad, the governor of Kassala state, denied having met the members of the NCP, which was officially banned after Bashir was removed from power.

The FFC and the RSF

On the paramilitary side, the FFC has been under fire from both the resistance committees and from leaders connected to the NCP, with both accusing the civilian leaders of siding with the RSF.

Supporters of the NCP also attacked resistance committee members in the eastern city of Gedaref, eyewitnesses told MEE, providing video evidence.

One resistance committee source said that national intelligence forces present at a counter-demonstration organised by a local NCP group in opposition to the resistance committees turned a blind eye to the attacks.

‘The RSF and the FFC have a joint aim, which is to climb to power through political compromise’

– Mohamed Badawi, Sudanese scholar

The FFC has established a “civic front” to campaign for the ending of the war, but sources in the resistance committees said there were signs the FFC is backing the RSF, as the mainstream civilian coalition is not clearly condemning the paramilitary’s violations – or at least drawing an equivalence between both sides.

Ibrahim, the resistance committees’ spokesperson, also accused the FFC of allying with and legitimising the presence of the RSF through its call for a political compromise before and after the war.

Before the war began, the resistance committees did not support the FFC-backed December 2022 framework deal, which they believed gave too much power to the army and the RSF, thus entrenching a rotten status quo.

“What they are doing is supporting the RSF through the political deal, so this will legitimise the RSF and the counter-revolution powers,” Ibrahim said of the FFC leaders.

“This is not a new attitude from the Sudanese political parties. There have been many uprisings in Sudanese history and political parties end up allying with the armed forces to cut off the revolution,” he said.

“We are against the air strikes committed by SAF and at the same time condemning the looting of houses and other violations committed by the RSF,” the FFC said in a press release, after a meeting of various parties in Cairo.

Former officials in the transitional government – established in 2019 and dissolved in the military coup led by Burhan and Hemeti in October 2021 – participated recently in a workshop in Lome, the capital of Togo.

Former justice minister Nasredeen Abdulbari and one-time sovereignty council member Mohamed Hassan Altaaishi, both technocratic politicians who have connections to the FFC, were at the workshop, which was organised by the RSF and attended by RSF officials, as well as elites from Darfur.

In a document obtained by the MEE, the workshop recommended the unification of Darfuri political and military power as a means of avoiding the slide into civil war in Darfur.

For Badawi, the Sudanese scholar, Islamic movements and the FFC are both trying to gain power “using different tools and tactics”.

“There are many clear signs of the Islamic movement and the deep state supporting the army, even since the ousting of Bashir and the formation of the sovereignty council,” he said. “This increased after the 25 October 2021 coup.

“The army and Islamic movement have used the national discourse in this war, and this is why they let the head of the army, Burhan, declare the opening of the military camps and recruitment for SAF,” Badawi said.

“The difference is that the RSF and the FFC have a joint aim, which is to climb to power through political compromise, while the army and the Islamic movement intended to use violence, including the military coup and the war.

“I don’t think the FFC is openly supporting the RSF,” Badawi told MEE. “But they do have common ground when it comes to how they gain power.”

Source : Middle East Eye

Add Comment